So here's an old photoset I'd lost track of at the bottom of my drafts folder. For any non-local readers, this is the Columbia Gorge's somewhat low-fidelity Stonehenge replica, built in 1918 as Klickitat County's World War I memorial. It was widely believed at the time that the original Stonehenge was built for human sacrifices, and I gather the memorial was meant as a sort of bitter comment that humanity hasn't progressed in the last few thousand years. Though the fact that they had the archeology all wrong kind of muddles the intended message. In any case, it's quite a scenic location and not at all depressing in person, and I thought some of my photos turned out ok, so here they are.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

Saturday, November 22, 2014

Monument Square, Lone Fir

Our next adventure takes us back to SE Portland's Lone Fir Cemetery, but we aren't looking at headstones this time. Instead we're taking a look at an obscure war memorial located in the middle of the cemetery. This was built circa 1903 as a Civil War memorial, organized by the Grand Army of the Republic, the main war veterans' organization. As this was not long after the Spanish-American War, the memorial also includes nods to the other conflicts, including, unusually, the Indian Wars. (Although given the date, it was probably only intended to honor the white, not the Indian, side of the conflict.)

Planning for the memorial began in 1901-1902, and it was dedicated on Memorial Day 1903. It wasn't actually complete at dedication, though, as the statue on top had yet to arrive. So a second grand ceremony was held in October for the unveiling of the statue. That article refers to the surrounding area as "Monument Square", and mentions that it was being dedicated or deeded as a public park. I'm not sure what that means, exactly, since PortlandMaps shows the area as legally part of the cemetery, not a separate parcel. The name "Monument Square" seems to have fallen out of use over the next decade, and doesn't occur in the Oregonian after 1916. But as far as I know that's still the legal, official name for the place, so that's what I'm going with as a post title.

Metro's 2008 "Existing Conditions & Recommendations Report" for the cemetery calls the area "War Memorial Park", and describes it:

The cemetery’s 1944 amended plat map designates the area around the Soldiers Memorial as a public park. The existing area of this delineated park contains the classic single monolith Soldier’s Memorial, three donor benches, and a later addition concrete slab that is currently being used for funeral services. The Soldier’s Memorial is made of granite with a bronze statue and bronze plaques. It is in stable condition, although the soil appears to have eroded away at the base, exposing some of the foundation in places.

The memorial was designed by local architect Delos D. Neer, who's best known for a number of historic county courthouses around the state, including the landmark Benton County Courthouse in Corvallis.

Details are sketchy about the statue on top. An article about the design simply mentions that it was bought from an unnamed eastern firm, which created a special model to the city's specifications. So there may or may not be other identical or similar copies out there, and it's hard to be sure because we don't know the firm or artist.

I had previously been under the impression this was a Spanish-American War memorial, and I think I've said something to that effect in a couple of earlier posts, I think in the context of marveling at how many Spanish-American War memorials Portland ended up with, like the Soldier Monument in Lownsdale Square, and the Battleship Oregon memorial in Waterfront Park. So I may have to go back and fix those older posts now. I also asserted once that the pair of Ft. Sumter cannons in Lownsdale Square was the only Civil War memorial in town, and obviously that isn't quite true either.

Miscellaneous items concerning the memorial from around the net:

- brief mention in Randol B. Fletcher's Hidden History of Civil War Oregon

- Waymarking page, with GPS coordinates in case you don't want to wander aimlessly around a cemetery looking for the monument.

- A post at Destinations Northwest

- A post at Blogging a Dead Horse

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Soldiers & Sailors Monument, Boston Common

A few photos of Boston's Soldiers and Sailors Monument, atop a low hill in the middle of Boston Common. It's a big allegorical Civil War memorial, like the later and more ornate Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Cleveland's Public Square. A page at Celebrate Boston describes the monument's allegorical odds and ends and what they all represent. CT Monuments laments graffiti and vandalism at the monument, and points out a nearby World War I monument made from a converted sea mine, which I'm quite sorry I didn't notice when I was there. Historical Digression talks about the monument a bit and moves on to Martin Milmore, its sculptor. Milmore died young at age 38, and was memorialized by Daniel Chester French's famous Death and the Sculptor, which may actually be better known than Milmore himself these days. French is best known for his Abraham Lincoln statue at the Lincoln Memorial, and he also created the Minute Man statue at the Old North Bridge in Concord, MA.

Public Art Boston's info page for the monument notes that "In honoring ordinary soldiers and sailors, rather than military leaders, this work set an important precedent adopted by the designers of subsequent memorials." and points out that it's available for "adoption" in the city's Adopt-a-Statue program.

On the point about this memorial defining a style for future ones, I came across a paper in the Spring 1988 Journal of American Culture, "Martin Millmore's Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on the Boston Common: Formulating Conventionalism in Design and Symbolism". It looks interesting but unfortunately it's paywalled, and I'm not a Real Historian who can get it through a university library, and JSTOR does't have it, so -- peon that I am -- I can only see the first page. So this is the part where I put in a plug for Open Access publishing. Here's the first paragraph, in the spirit of fair use, since that hasn't been abolished yet:

The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument on the Boston Common, designed by Martin Millmore and erected 1870-1877, is one of several types of memorials elevated after the Civil War. The characteristics of this monument, its configuration and iconography, were influenced by popular ideas and eclectic stylistic trends in post-Civil War America. The shaping of this type of monument was especially influenced by the popular tastes of the period. An analysis of the style, sources, and imagery of the design offers insight into the ideologies, the formulating conventions of the age, and the role of the artist in satisfying the prevalent demand for military monuments as art within the public domain.

Without really intending to, I've ended up with a handful of posts here about Civil War memorials. Beyond this one and the one in Cleveland, I've also got Southern contributions to the genre in Edgefield, SC and Tupelo, MS, as well as Portland's own very humble contribution, a couple of puny surplus cannons in Lownsdale Square. So I figured I'd go ahead and add a "civil war" post tag, so it's one stop shopping for visitors who just can't get enough of the Civil War for whatever reason. I don't get that, personally, but I like to feel I'm providing a valuable service here, even when I find it inexplicable.

Monday, February 17, 2014

Memorial Column, NE 13th & Burnside

View Larger Map

A few years ago, the city of Portland finally did something about the accident-prone intersection of East Burnside, Sandy Boulevard, and 12th Avenue, after a few decades of the public complaining about it. Not everyone loves the resulting Burnside-Couch couplet, but at least the one crazy intersection isn't so crazy anymore. The change involved closing the 2 block diagonal stretch of Sandy between 12th and 14th, as well as one block of NE 13th between Burnside and Couch. The resulting two-block area is supposed to be redeveloped someday, presumably into upscale condos or something. The couplet was the previous mayor's baby and the whole thing seems to have lost momentum after the last election. So for the most part the traffic flow shift is the only thing that's changed so far.

One thing they've managed to do here is jackhammer up part of the former 13th Avenue and turn it into a meandering bioswale, thanks to the city's ongoing obsession with stormwater management. At the Burnside end of the bioswale is a tall metal sculpture with a series of stainless steel fins projecting up from a concrete block. You may have guessed from the post title (and from the general artsy theme I've been running with lately) that this sculpture is why we're here. I noticed it when driving past on Burnside a while back, made a mental note of it, and later tried the usual sources to see what I could find out about it. Searching RACC, the Smithsonian art database, and the library's Oregonian database all came up with nothing. No news stories, no press releases from the city, nothing. When I went to take these photos, I looked all over for a sign giving a title, maybe an artist, something explaining what it's about. I couldn't find a sign, so no luck there either.

So after searching the entire internet, I've found precisely two city documents that mention it. Because we're a deeply process-oriented city, the city's Transportation Bureau had to get a permit from the Bureau of Development Services (a.k.a. the city planning department) before proceeding with the bioswale project. The first pdf (containing the city's official approval of the plan) includes a diagram that calls it Memorial Column, and credits it to Lloyd D. Lindley and Nevue Ngan Associates, while the second (the city's permit application) includes detailed schematics. I see that the sculpture was created by urban designers and landscape architects, so it looks like the local public art community wasn't involved here. Which I guess would explain why it's not in the RACC database. The approval doc explains that the bioswale might be only temporary, assuming the eventual swanky condo towers come with bioswales of their own, but the sculpture has to stay, regardless. The approval further explains "The tall vertical element reveals this important place from a few blocks away" and "As a memorial to a PBOT employee, the proposed column integrates Portland as a theme". The phrasing there is because the city planners have to explain how the design furthers their design goals, and "integrating Portland as a theme" (whatever that means) is apparently one of those goals.

So that's all I know. There are some obvious open questions: Who is this a memorial to? And why? There's obviously more to the story, but for the life of me I can't seem to answer those questions. You'd think there would have been a press release, a dedication ceremony, maybe some news stories, adoring quotes by former PBOT coworkers praising the honoree perhaps. But I can't find any record of any of these things. That seems like an odd oversight, if it was an oversight. And if it wasn't an oversight, but an attempt to downplay the whole thing, that would raise additional questions. I have no idea. As always, if you happen to have the missing puzzle pieces in your possession, feel free to leave a comment below and help sort out the mystery. Thx. Mgmt.

Saturday, January 25, 2014

Oregon Korean War Memorial, Wilsonville

A few photos of the Oregon Korean War Memorial, in Wilsonville's Town Center Park, one of a small number of Korean War memorials around the state.

You might notice that, along with the US, Oregon, and POW/MIA flags, the memorial flies a United Nations flag. The flag's there because the war was fought under the banner of the United Nations Command, and the same UN organization is technically in charge of forces in South Korea to this day (though in actuality it's only been US and South Korean forces for decades now.) To be honest, a big reason I stopped was to see whether the UN flag was still there or not. Shortly after the memorial opened, there was an ugly episode of right wing hysteria about the UN flag flying at the memorial, with the usual Bircher mutterings about one-world government and so forth. There doesn't seem to have been a repeat of the episode, or at least it hasn't made it into the Oregonian since then.

Sunday, November 17, 2013

Logan Airport 9/11 Memorial

[View Larger Map]

When I was in Boston a while back, I spent a couple of nights at a hotel right at Logan Airport, a short skybridge trek from the main terminal. It turned out that the airport's 9/11 memorial was across the street, so I made a brief visit to it. Both of the planes that hit the World Trade Center towers took off from Logan Airport, and many of the passengers and crew aboard the planes were from Boston, so a memorial of some sort was obviously needed. But dealing with such a sensitive topic wouldn't be easy, and the local authorities didn't rush it. The memorial didn't open until 2008, and it's striking for how delicately, even gingerly, the memorial design treats its subject. I'm not sure I would have found it at all if my hotel hadn't been next to it. It's not in a place where airport visitors will stumble across it unexpectedly while going about their business. It has to be sought out deliberately. If you persevere and locate it, you'll see a landscaped plot with several paths, and a small glass cube set well back from the street. There's a small plaque indicating this is the memorial, and an inscription on the sidewalk refers obliquely to "the events of September 11th, 2001". The long winding paths aren't in any hurry to get you to the cube, and meander around the landscaped area. When you get to the cube, nothing about its exterior says "memorial" at all. Only once you're inside do you see the lists of names of those on the two flights. As you might imagine, the memorial's lightly visited. In the few days I was there, I didn't see a single person (other than myself) visit it.

Of course not everyone's a fan. It made a conspiracy site's list of the "Top 5 Worst 9/11 Memorials", which points out that this memorial strongly resembles an Apple store. I will allow that this is true. It's actually a decent list, and a couple of the others on the list are genuinely terrible. Although from the site's standpoint anything that doesn't say "false flag" probably counts as a bad memorial.

I started out thinking this was a strange memorial myself, and considered writing a snarky post complaining about it. Then I started thinking, ok, what would I have done differently, if somehow I'd gotten the job to design it? Would it be a better memorial if it didn't tiptoe around the subject quite so much? Maybe if it was somewhere in the airport where travelers -- who might be afraid of flying anyway -- could stumble across it and be surprised? If it was anything at all like the hideous 9/11 memorial in Portland that I griped about a few years ago? Well, no, none of the above. I get that it's a sensitive topic. This post sat around in Drafts for about a year, while I tried to figure out the right tone and the right timing. I didn't want to post it near 9/11 (since I've already said everything I ever want to about that day), or too close to any of our many military-themed holidays, and then I put it on extended hold after the Boston Marathon bombing so as not to seem exploitative. So like the actual designers, I'm pretty sure I would have erred on the side of endless trigger warnings and chances to back out, and the most understated and least graphic treatment I could pull off without seeming to downplay the "events". And I probably would have said "events".

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Battle Green, Lexington

[View Larger Map]

It's time for another set of Boston photos, this time from the town common in Lexington, MA, commonly known as the Battle Green due to the Revolutionary War battle that happened here on April 19th, 1775. I lost track of how many monuments, statues and plaques there were in the common itself and the surrounding neighborhood. This photoset includes many prominent examples, but I'm sure I missed a few. Beyond this historic district, though, Lexington comes across as an average suburb. That really shouldn't have surprised me, but it did somehow. As with the Old North Bridge a few miles west in Concord, the modest scale of everything is striking. For all its eventual historical importance, the number of people actively involved at any point in the entire war was quite small. I don't mean to go off on a history lesson here; if you're curious, and somehow missed the entire term of 8th grade history that covered the American Revolution, or you grew up outside the US, there are much better sources of information than some random internet blog. I just wander around taking photos and trying to describe what's in them. For more obscure topics, the describing part involves linking to "authoritative" sources, which can sometimes be hard to find. As for Lexington, though, perhaps half of all the historians in America have already written a book or two about the Revolutionary War, or so it seems. There's a vast range of facts and opinions out there, and you can google for it just as well as I can. But feel free to enjoy the photos while you're here though.

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Fountain for Company H

Today's adventure takes us back to downtown Portland's Lownsdale Square again, this time to an ornate century-old drinking fountain on the 4th Avenue side of the park, which the city describes as:

Another memorial dedicated to the men killed in service in the Philippines, Fountain for Company H, was installed in 1914. It was donated by the mothers, sisters, and wives of the men in Company H of the Second Oregon Volunteers. John H. Beaver, an architectural draftsman, won the honor of designing the limestone fountain and a $50 prize in a citywide contest.

This is yet another of the city's numerous Spanish-American War memorials, which include the Soldiers Monument at the center of Lownsdale Square, the Battleship Oregon Memorial in Waterfront Park, and a monument in Lone Fir Cemetery. (The latter is primarily a Civil War memorial, but includes a nod to various other conflicts up to 1903 when it was built, including the Indian Wars.) I've heard that yet another monument exists somewhere in the West Hills near the VA Hospital, but I don't know a lot about that one.

The fountain was unveiled on September 2nd, 1914. Much of the Oregonian article about the dedication is the text a poem read at the dedication, an earnest prayer for peace. It's worth noting that World War I had begun just a month earlier.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Soldiers Monument, Lownsdale Square

A photoset of the 1906 Soldiers Monument in Lownsdale Square, one of the city's surprising number of Spanish-American War memorials. A post over at Dave Knows PDX gives a little history of the monument.

The memorial was designed by the famous San Francisco sculptor Douglas Tilden (1860-1935). Tilden was deaf since the age of 4 and had a very successful career in what's thought of today as a not very accommodating era. Tilden was also rumored to have been gay, which (true or not) is bound to infuriate the sort of person who usually loves war and war memorials, even in this enlightened post-DADT era. These would likely be the same people who freaked out when someone used a little temporary chalk on and around the monument's base during the Occupy Portland protests last year, which you'll see in a few photos in this set. They shrieked on and on about how the memorial had been permanently defiled or destroyed or something, when in reality no damage, either permanent or temporary, was actually done to it. I imagine their heads would explode if they heard the rumors about the sculptor. Maybe they'd sue, or invite Fred Phelps to come protest the statue, or something.

More about Tilden and his Bay Area works at Found SF and SF City Guides.

A 1951 Oregonian article "Portland's Outdoor Statues" (July 8th, 1951) lists it among the city's "important" public art pieces. The others included the Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt statues on the Park Blocks, and the Thompson Elk between Lownsdale and Chapman Squares, as well as the Thomas Jefferson statue at Jefferson High School, and a religious statue out at the Grotto. While I'm linking to old blog posts, I should point out that two previous subjects are right at the Soldiers Monument: The Ft. Sumter Cannons, and Benchmark Zero. So if you go to Lownsdale Square to look at the statue, you might as well look down and see those as well.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Soldiers & Sailors Monument, Cleveland

A few photos of Cleveland's Soldiers & Sailors Monument, the Civil War memorial in Public Square. Wikipedia's extensive "Ohio in the American Civil War" article should give some idea why the city built such a large and ornate monument.

These were taken on a cold, windy day back in March, but I wanted to post some Cleveland photos today for the city's 216th birthday (216 also being the local area code, you see).

View Larger Map

Sunday, March 07, 2010

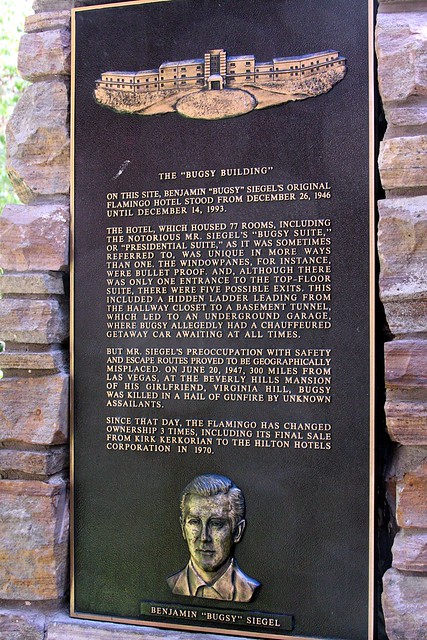

Bugsy Siegel Memorial, Flamingo Las Vegas

On the grounds of the Flamingo Las Vegas casino, between the pool and one of the wedding chapels, there sits this small memorial to the hotel's founder, the notorious mobster Bugsy Siegel. The plaque has a colorful bit about the original hotel building, none of which survives today. There's a bit about Siegel getting whacked in LA, and the sign concludes by pointing out that the hotel's changed hands three times since then, just to be clear that, as glamorous as the Mafia was back in 1946, current management is Definitely Not The Mafia. Actually the Flamingo has changed hands one more time since the memorial went in, and it's now part of the vast Harrah's empire.

A lot of people see or hear about this marker and go, "Only in Las Vegas". Some people find it scandalous that the Mafia plays such a big part in the city's creation myths. But, c'mon, it's not like Vegas is the only place that likes a little naughtiness in its past. Lots of cities do that, and it doesn't have to be far in the rear view mirror before people start romanticizing it. Tampa has its pirates. LA has shady silent-movie types, ready to flee to Mexico at a moment's notice, half a step ahead of the law, or creditors. All of Australia has the whole convict thing. Silicon Valley has amusing tales of not-strictly-legal geekery, like Apple's pre-origins making phone phreaking gear. New Orleans has, well, everything. Even Portland gets notions about having once been a lusty seaport, where unsuspecting men were shanghaied and pressed into service on ships bound for the South Seas or around Cape Horn. We'll never know for sure how common that actually was. Even if it was just an occasional practice, in terms of sheer nastiness it would rank right up there with anything the Mafia ever did. But it makes for an entertaining myth, and tourists pay to hear fanciful tales about it, and it's not really hurting anyone at this point. So I can't really get worked up about it when Vegas does the same thing.

Years ago I had a boss of, well, Sicilian extraction, who once told me about an uncle of his back in Boston. He was everyone's favorite uncle, friendly, generous, always had gifts for all the kids, always dressed impeccably in expensive suits. The one rule was that you were to never, ever inquire about what he did for a living. The boss left the story at that, but I always got the impression he knew a lot more than he cared to say. So in a way, I once knew a guy who knew a guy, you know what I'm sayin'?

Tuesday, March 02, 2010

Ft. Sumter Cannons, Lownsdale Square

Downtown Portland's Lownsdale Square is often overlooked, and the war memorial at its center is even more obscure. The main feature of the memorial is a pillar topped with a statue of a soldier, commemorating the Spanish-American War (which itself is a bit obscure). At its base sit two very small cannons, one facing north and the other south. They don't look like much, and practically nobody notices them, but it turns out they're one of Portland's two obscure Civil War memorials, the other being a monument in the middle of Lone Fir Cemetery.

A plaque on one states "HOWITZERS USED IN DEFENSE OF FORT SUMPTER 1861". In case you played hooky that day in history class, Fort Sumter (no 'P' ) is a fortified island in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The Civil War started there, with Confederate forces laying siege to the Union-held fort. Later in the war the roles were reversed for a second siege.

The Parks Bureau page for the square (link up above) explains:

At the base of this monument are two small cannons from Fort Sumter (misspelled on the plaque) brought here by Colonel Henry E. Dosch. Because the cannons were used by both Union and Confederate troops, it was Dosch's idea to face one north and one south.

If I cared to look for it, I'm sure there's all manner of trivia available about these cannons: Who made them and when, what sort of ammunition they used, maximum range, that sort of thing. But I'm really not very interested at all in the military history angle. I'm not a huge war fan, much less one of those historical reenactor guys who like to put on costumes and pretend to shoot each other. That stuff kind of creeps me out, to be honest. It's more that a.) the cannons are uncommonly old by Portland standards regardless of what they are, and b.) it's a rare opportunity for me to plug Charleston, which is an amazingly beautiful and historic city.

But don't take my word for it about Charleston; go see for yourself, or at least fire up Google Street View and have a virtual wander around the city. You can even go visit Fort Sumter in person if you want to. We did, years ago, but you really have to use your imagination to picture what happened there. Really there are far more interesting things to see and do in Charleston, although the boat trip cross the harbor is pretty scenic. So there's that.

I'm more interested in why and how the cannons came to Portland. I'd really like to be able to point at a news story or book excerpt explaining this, but I haven't found anything like that on the net. We can, however, look at the gentleman who brought the cannons here, and make some educated guesses from there.

RootsWeb has a couple of period bios of Col. Dosch: Charles Henry Carey's History of Oregon (1922) and a 1903 book titled "Portrait and Biographical Record of Portland and Vicinity, Oregon". It's your basic "German bookkeeper immigrates to US just in time for the Civil War, joins up, has adventures, gets wounded, leaves the Army, heads west, has adventures, does a stint as a Pony Express rider, ends up in Portland, goes into business, eventually retires, spends later years as an amateur horticulturalist, when not managing exhibits at World's Fairs around the globe." type story. Although you have to admit that's kind of an unusual story.

The University of Washington library has two photos of Dosch in 1909, and he looks exactly the way you (or at least I) would imagine a World's Fair bigwig would look.

Among other things, Dosch organized the Oregon exhibit at the 1901-1902 South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in Charleston, which just might be when and where he obtained these cannons. One goal of the fair was to publicize our newly conquered colonies the US picked up in the Spanish-American War (The Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, etc.) So it may have seemed less peculiar at the time to situate Civil War cannons around a Spanish-American War monument.

A few other tidbits about Col. Dosch, from across the interwebs:

- At one point he wrote a book, or at least a pamphlet: "Vigilante days at Virginia City: Personal narrative of Col. Henry E. Dosch, member of Fremonts body guard and one-time pony express rider", which sadly doesn't seem to be online anywhere.

- The Henry E. Dosch Family Collection resides at the Multnomah County Library, and Portland State University students have taken on sorting and organizing the collection, apparently for college credit. Which is to say, it's probably a total meat market, with a bit of filing and organizing on the side. The site doesn't mention any part of the collection being online. Maybe they'll get around to that someday.

- A few items relating to Col. Dosch in the Charles L. Emerson Collection at the University of West Alabama library. Not sure what the Alabama connection is, and none of these documents are online either.

- Snyder's Portland Names and Neighborhoods states that SW Portland's Dosch Road and a couple of minor streets nearby are named for Col. Dosch.

- Home Orchard Society: "All About the Apple Called Yellow Bellflower" mentions Dosch's apparent role in the survival of a very old apple variety, one that may have come to Oregon via the Oregon Trail.

- Oregon Historical Society: A rather curt letter Dosch wrote to a job seeker, in his capacity as the Lewis and Clark Exposition's Director of Exhibits.

- A bit of family drama somehow made the New York Times, on November 6, 1912: "WEDDED AFTER THREE DAYS.; Margaret Dosch of Portland, Ore., Runs Away with B.S. Jossellyn's Son." It sounds like a typical love-at-first-sight and then elopement story. I don't really see why the NYT would have found this newsworthy. It's not like New Yorkers would have found this terribly shocking, even in 1912.

One other loose end to sort out is the plaque's misspelling of "Sumter" as "Sumpter". As it turns out, there's an old mining ghost town in Eastern Oregon also named (and spelled) Sumpter. That's the only other case I've seen of "Sumter" being spelled with a 'p', so I suspect there's a connection. I'd guess people in Portland were so used to spelling it with a 'p' that they just did it without thinking. The classic "Oregon: End of the Trail" (from the Depression-era Federal Writers Program) describes the town in poetic and alarming terms:

Right on this road along the north bank of Powder River to SUMPTER, 19.6 m. (4,424 alt.), an almost deserted town of the "hard-rock" mining era. In 1902 an editorial in the local paper asked- "Sumpter, golden Sumpter, what glorious future awaits thee?" The answer today is a U. S.Forest station, one store with a pool hall, and the crumbled remnants of a business section that once stretched seven blocks up the steep hill. The town was so named because three North Carolinians, who chose a farmsite at this point in 1862, called their log cabin Fort Sumpter a misspelling of "Sumter." For many years the camp existed by grace of the few white miners who explored the district and hundreds of Chinese who followed them. With the coming of the railroad in 1896 and the opening of ore veins on the Blue Mountains, Sumpter became a city of 3,000 inhabitants. The total yield of the Sumpter quadrangle from both placer and deep mines has been nearly sixteen million dollars Names of the most productive mines were Mammoth, Goldbug-Gnzzly, Bald Mountain, Golden Eagle, May Queen, Ibex, Baby McKee, Belle of Baker, Quebec, White Star, Gold Ridge, and Bonanza. Twelve miles of mine tunnels were in operation at one time The town even had an opera house where fancy dress balls were held, but the sheepmen of the region were not welcome at them. The vigilante committee warned sheepmen away from the gold country on the threat of fixing them up "until the Angels could pan lead out of their souls." The story of Sumpter after 1916 is almost a blank. The few people who remained became accustomed to the sound of crumbling walls and to using doors and window frames for firewood. The smelter erected during the last days of the boom still stands. Pack rats live in the vaults of two former banks.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Chas. B. Merrick Memorial

You probably don't remember this, but about a year ago I tracked down Portland's obscure George Washington statue, at the corner of NE 57th and Sandy. While I was there, I took a few photos of an even more obscure & curious drinking fountain near the statue, marked simply "CHAS. B. MERRICK MEMORIAL A.D. 1916". My gut feeling was that looking for info on Mr. Merrick was likely to be a dead end, which happens a lot. So I didn't pursue the matter until now. But it turns out we're in luck this time, and I can answer a multitude of questions you didn't know you were about to ask.

Charles B. Merrick was a civic leader in early 1900s Portland, and the 1911 book "Portland, Oregon, its history and builders" has a brief bio. Your basic Spanish American War vet / grocer / insurance executive (of the "Beaver State Merchants' Mutual Fire Insurance Association", organized 1908 ) / postmaster, and general pillar of the community. In his capacity as community pillar, he figured in the city's early urban planning efforts, lobbying the city and the public to adopt the Bennett Plan. And as postmaster, he was behind early experiments with airmail, where a pilot flew batches of letters from Portland all the way to Vancouver WA. That's more of a big deal than it sounds, actually, since the Interstate Bridge hadn't been built yet.

The bio I linked to earlier said this of Merrick:

Born in Saginaw, Michigan, July 30, 1873, Mr. Merrick is thirty-seven years of age and may be said to have just fairly entered upon the possibilities of a long and useful career.

Sadly, Merrick died shortly after this was published, in August 1912, at Lakeview OR. He was 39 years old plus a month or so, or almost exactly my age right this minute, which is a tad spooky. The circumstances of his very untimely demise aren't noted in any of the online sources I've found, but I see that an area newspaper, the Alturas New Era, printed an obit dated August 28th. And the Library of Congress has a list of libraries that have the New Era on microfilm for this time period. None are local, unfortunately. But the answers are probably out there if some dedicated researcher wants to track them down.

A rootsweb blurb gives a little more info: Died August 21st in Lakeview, buried August 26th at Mt. Calvary Cemetery in Portland. They actually have a search tool on their website, and it seems he's located at Section E, Lot 200, Space 1.

The one thing I haven't found any info about so far is why he has a drinking fountain dedicated to his memory. I don't know who put it up, or why. I mean, I suppose being a community leader and having an untimely demise of some sort might be enough. And I admit I sort of like the idea of people who die at 39 being remembered for being youthful and for the bright future they had ahead of them. But still, I'm not able to tell you who put the fountain here, which is too bad. Surely that's answered as well by old newspapers on microfilm. But it only gives the date 1916, so until someone scans and OCRs papers from that era you'll be looking through a whole year's worth of Oregonian issues on microfilm, hoping there was a news story at the time. And since it's 1916, you'll be reading a great deal about World War I while you're at it, and that will be depressing. So this may be another chore for some avid researcher.

Updated: The scanning and OCRing has occurred, and the Oregonian historical database now has a few some answers for us. A lengthy obit ran on August 22nd, 1912, "LATE POSTMASTER BORN POLITICIAN", where the word "politician" is used in a complimentary sense. It appears the fountain really was created just because he was a well-liked pillar of the community who died young and suddenly. No cause of death is given, although my understanding is that this was not unusual in 1912. Except, of course, when a poor person died in lurid circumstances. Then it tended to be front page news. But that's another blog post entirely.

An August 18th, 1912 article states that Merrick and a number of other prominent citizens were setting off on an excursion to Lakeview to attend the convention of the Central Oregon Development League, whatever that was. Going to Lakeview by car was quite an undertaking in 1912, it seems, as the article goes on at length about everyone who was going, what routes they were taking, and the heroic efforts to make sure everyone had a map. Merrick and his party journeyed to Lakeview via Burns. That isn't exactly a direct route from Portland, and involves driving through what is still empty, rugged terrain.

A February 18, 1917 story about the dedication of the fountain includes a photo, which shows us that the fountain was once topped by some sort of urn or planter. It appears to have been metal of some sort, so my guess is that someone over the last near-century decided it was valuable and made off with it.

Monday, December 14, 2009

Monday, November 16, 2009

Vernon Ross Veterans Memorial

View Larger Map

At the corner of NE Sandy, Thompson, and 48th Avenue, out in the Hollywood District, is Portland's Vernon Ross Veterans Memorial, a small monument with a very tall flagpole. I'd never heard of it until I ran across a brief mention of it in this brief document from the Parks Bureau, in which we learn when they did maintenance of some sort on various obscure spots around town. I was actually looking for info on the park at Hall & 14th, and the doc didn't tell me anything useful about that place, but it's full of other places I haven't covered yet. When I saw there was some sort of obscure memorial in town that I'd never heard of, I knew I had to track it down.

Or at least I started out by assuming it was obscure, since I'd never heard of it before. But as it turns out, it has a fairly prominent role once a year. Every year, Portland's Veterans Day parade winds through the Hollywood District and ends up right here, and the flagpole serves as the backdrop for speeches by various dignitaries and elected officials, generally including the mayor. This year marked the 35th edition of Portland's parade, the first coming in 1974 -- coincidentally when the Vernon Ross memorial was dedicated. As for the identity of Mr. Ross, the plaque here indicates he was the instigator of the memorial, rather than its subject as I originally assumed. The memorial itself doesn't explain who Vernon E. Ross was or why he was involved, but right across the street is the Ross Hollywood Chapel funeral home, which happens to be the longtime primary sponsor of the Veterans Day Parade. So I think that answers that question.

Updated 3/29/11: Thanks to the magic of the library's Oregonian historical archives, there are a few more details to relay. A July 12, 1974 article is titled Smallest block in city location for memorial. No, really, this spot is legally a platted city block, and it's our smallest, or at least it was in 1974. 48 square feet. The article says Ross bought the plot in part to prevent signs from being erected there. Ross also states that the plot is dedicated to the memory of Louis M. Heinrichs, a fellow World War I veteran.A followup article on September 18, 1975 covers the donation:

Ross ... said he purchased the 7-by-15-foot piece of land for $3,200 and paid $19,000 to erect the flag memorial.

"The patriotism of our country has gone to the lowest level that it's been in our history," he told the City Council Wednesday.

Mayor Neil Goldschmidt praised Ross' efforts to improve the land as being "in the best tradition" of the city.

Ross died in November 1983. His obituary says he suffered a heart attack during the Hollywood Veterans Day Parade.

For a time the memorial was referred to by name as either "Ross Veterans Memorial" or "Ross Memorial Park", but both had fallen out of use (at least by the Oregonian) by the mid 1980s.

KATU has a short video clip of this year's parade, and there's an article with a photo slideshow at Salem-news.com, although neither piece shows the memorial.

One of the questions I often try to answer about various places is "Who owns it, and who runs it?" Ok, maybe that counts as two questions. Anyway, a few references around the net (like this one) refer to the place as the "Ross Hollywood Chapel Veterans Memorial Flag Pole", but the tiny triangle of land actually belongs to the city. Although my guess is that someone comes over from next door rather than from city hall when it's time to raise or lower the flag here, or tend to the roses. That might explain why the city barely mentions it anywhere on their website. The Parks Bureau doesn't list it in their inventory, for one thing. Also, a few years ago there was a proposal to erect a new war memorial on Mt. Tabor, and as part of the process the city compiled an extensive list of existing veterans memorials across Oregon. It mentions small monuments in the far corners of the state, but fails to mention this one. So we can assume the place isn't exactly on everyone's radar at city hall. Not that veterans monuments are the city's cup of tea, really. The monument, you may note, went up in 1974, at the tail end of Vietnam, and I wonder if it went up in part as a way of shaking a fist at the dirty hippies or something. And then the dirty hippies went on to take over the city and they've been running it ever since. Also, since January we've had a mayor who'd be quickly booted out of the military on account of being gay, and despite that it's still part of his job to put in appearances at events like this. His official blog doesn't mention the event at all, so I don't know how he felt about it, but it must've been deeply weird.

In any case, PortlandMaps knows the place as R259400, 48 square feet of land officially owned by the City Auditor's office. (Although I think that's just a way of saying it's general city-owned land not belonging to any particular department, or they just haven't bothered to record which department it belongs to.) In any case, 48 square feet is pretty tiny, but it still comes to 6912 square inches, compared to 452 square inches of Mill Ends Park. That's 15.3 times bigger. FWIW.